The last year has also changed his view of social media. "It's really showed me that it's so important to be in person with people," he said.

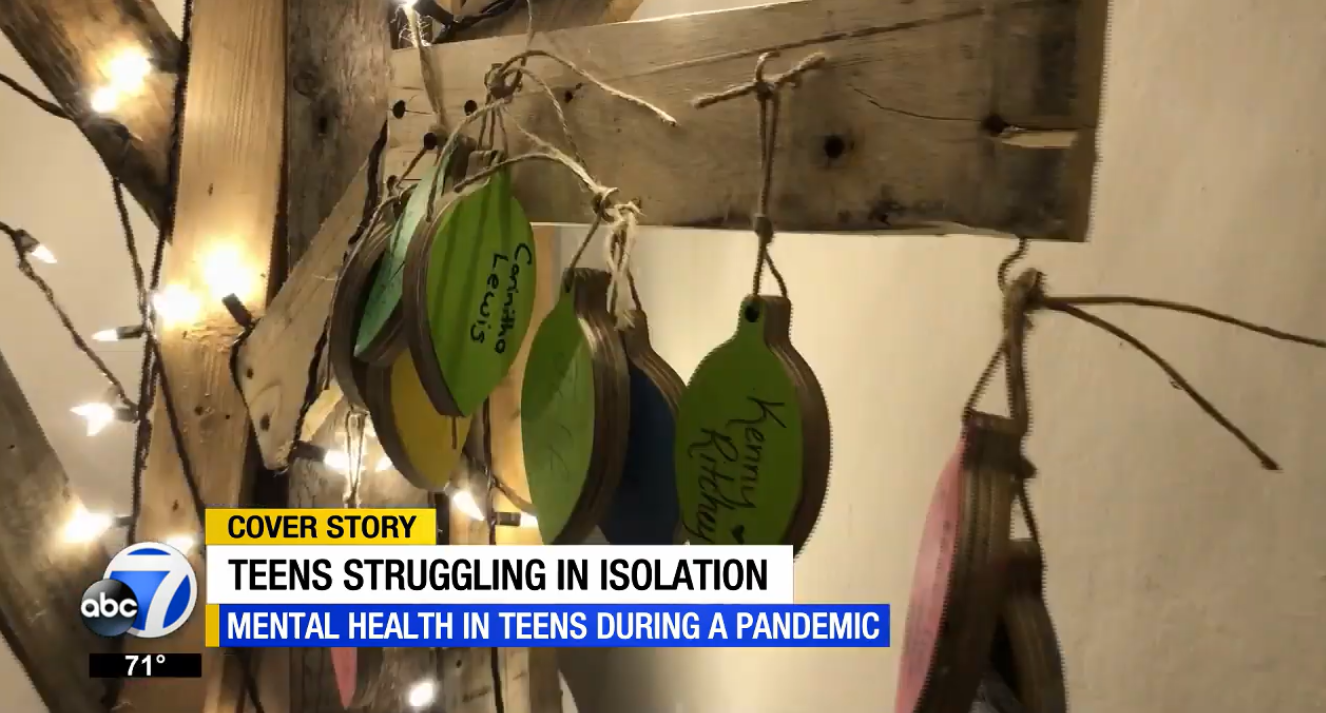

Angela Melvin, founder of Valerie's House, a Lee and Collier support service founded in 2014 for children and families who have experienced deaths in their families, said she has seen a noticeable increase in children struggling because of the pandemic.

And, in a worrying first, she said she's heard from "several" families who had a loved one under 13 die by suicide.

Families in those cases are convinced that isolation, and too much time spent on social media, played a role, Melvin said. That, coupled with continuing news about the pandemic and political unrest, is taking a toll, she said.

"You have social unrest, you have the presidency, and just the meanness back and forth. And then you have the violence and you have the fear of dying — you know, are their parents going to die or their grandparents are going to die, walking around with something covering up their face 24/7," Melvin said. "Can you imagine taking that on as a 10-year-old right now?"

A shortage of services

Southwest Florida mental health agencies, hospitals and law enforcement have long lamented the shortage of mental health services in this region. But the problem isn't limited to just this area.

Florida ranks last among states in per-person funding of mental health services. The state's $36 per person in spending is ahead of only one U.S. jurisdiction, Puerto Rico, where the per capita spending is about $20.

Low funding means less money to expand mental health facilities and pay for qualified mental health counselors, staffers and, particularly, psychiatrists — a profession already not keeping up with demand for services. Many can also find much higher wages elsewhere.

Lee County has one mental health provider for every 930 people, an improvement from recent years but well short of the state average of one for every 620 and top-performing U.S. communities with one for every 290, according to the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

In Collier County, the rate is one for every 1,000 residents, according to the Population Health Institute. That's roughly the rate it's had for years.

Mental health providers who specialize in care for children are in even shorter supply, local health care experts say.

"We had a pretty significant mental health crisis prior to COVID: depression, anxiety, suicide, complex trauma, domestic violence — all that sort of thing," said Paul Simeone, vice president of mental and behavioral health for Lee Health. "COVID just took everything and amplified it. So all of the symptoms that were present have gotten much worse, across the board."

More:'It's a double-edged sword': Survey says young Americans are using social media to address mental health issues ... caused by social media

A crisis without end:Florida ranks last among states in spending for mental health

Expanding mental health care

The sharp growth of children's' mental health care needs does come as Southwest Florida continues to slowly expand services.

Though they're often at capacity, mental health crisis units in Lee and Collier have expanded in recent years by adding a handful of beds. They can now, combined, house more than 30 children.

Nearby Charlotte Behavioral Health, which also expanded five years ago, has a 30-bed unit to use for children or adults.

Five years ago, Lee Health had a single inpatient psychiatrist. Then, in 2018, Lee Health launched its "Kids' Minds Matter" initiative to expand mental health services for children and make it a major piece of its fundraising efforts.

Since then Lee Health has hired 29 new mental health providers, including five psychologists, three pediatric psychiatrists and two mental health counselors. It also offers a variety of services, including a LGBTQ+ group for teens ages 13 to 17 in Lee, Collier, Charlotte, Hendry and Glades counties.

"One of the main factors in the increase in the number of visits is the addition of new providers which has improved access to these services for children," Lee Health spokesman Jonathon Little said.

But Simeone says that expansion in services is not keeping up with demand.

"Even though we've increased the (patient) visit rate at Golisano by 3,000% over the last couple of years, there's still a six- to eight-week wait," he said. "It's frustrating."

The pandemic has also led to a dramatic expansion of telehealth services, including in the mental health realm.

"Telehealth can be very effective if that's all we have available," said Dauphinais of The David Lawrence Center. "We have capacity for individuals to participate through that. So, help is available."

Frank Gluck is a watchdog reporter with The News-Press and the Naples Daily News. Connect with him at fgluck@news-press.com or on Twitter: @FrankGluck